Golden Rules

The cast of my own memoir includes plenty of dead people, but one of the live, off-camera characters who has helped shape my book is the author Claire Bidwell-Smith.

In addition to being 30-something and a former New Yorker, her just-released memoir, The Rules of Inheritance, also stars several dead people. Her parents, specifically. By the time she was 25, cancer would claim both their lives. In this book, Claire explores life, loss and love with a candor that leaps through time and space to find a home in your own head. Her sepia-toned words shift between haunting and self-deprecating—with turns of phrase that compel underlining or memorization.

While in New York City this month to record her audio book and attend launch parties for Rules of Inheritance, Claire shared her behind-the-scenes process for creating one of the most powerful and technically stunning memoirs I’ve encountered.

TMR: You organized your story into five sections named for Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief. How did you arrive at this technical decision? Did it happen as a classic eureka moment or was it a slow build?

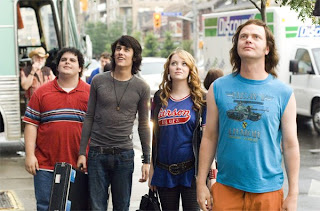

Claire Bidwell-Smith: It was an evolving process, really. I’d written two other versions of the memoir, both told in a much more linear and conventional fashion. Both of them came across quite boring. Part of the idea for breaking up my story into non-linear sections came after I saw the film "500 Days of Summer" with my husband. Afterward, he turned to me and said, you should really think about doing something unconventional like that. A few months later I decided that I wanted my story to have a pretty serious focus on grief, and decided to use Kubler-Ross’s stages.

I think there’s this tendency with memoir to tell the whole story. As in, you start in childhood and go all the way up to the present. At least in my case that initially seemed like the only option, especially given that I’m not very old so I don’t have a long life to write about. But when I used this approach, the past drafts ended up with a lot of unnecessary stuff. Paring the story down into these vignettes that fit into Kubler-Ross’s stages helped me to eliminate a lot of stuff that just wasn’t necessary.

TMR: As a storyteller, you have an uncanny instinct for balancing your tendency toward self-destruction with a capacity for self-realization. Just when your pain is almost too difficult to witness, you jump-cut to the smarter, healthier, less messy person you have become. Can you share your process for striking this narrative balance so effectively?

CBS: Part of it comes from the choice to write in the present tense at all times. Even when I was writing about a time in my life that took place when I was eighteen, I wrote in present tense. Doing this gave the story an immediacy that’s more difficult to achieve when writing in past tense. But it also allowed me to throw in little sneak peeks to the future.

For instance, when writing about a boy who hurt me in Chapter One I write: Right now I am simply confused and deeply hurt. It is only years later that I will be able to recognize what it was like for him to walk into my world the way he did. It is only later that I will understand that my grief was too much for him. Right now the only thing I can think about is how incredibly alone I am in all of this.

I think some of this balance also comes from writing this book at the right time. It takes time to have perspective on the things that happen to us in our lives. Ten years ago, when I began writing it, I was still right in the thick of the story. I simply wasn’t quite ready to write because I was still living it.

TMR: In addition to achieving balance, your jump cuts between time and space create a suspenseful undercurrent. As you wrote the first draft, did you write in a non-linear fashion or were these jump cuts a product of the editing process?

CBS: The jump cuts were the plan all along. Once I decided to use the five stages as the narrative structure, I wrote a complete outline. Each stage contained three chapters that exemplified that stage. For example, the Denial stage has chapters that take place when I was 18, 14, and 25 years old. I went into the writing knowing this and worked diligently off my outline. It was the first time in my life I really stuck to an outline—and it was incredibly helpful.

TMR: What was the most challenging aspect of writing The Rules of Inheritance and how did you conquer it?

CBS: I think the hardest part was writing it as honestly as I did. I’ve read every memoir I can get my hands on and I’ve decided that what makes the really good ones good is when the author is as absolutely honest as possible. But this isn’t an easy feat. I had to put a lot of people out of my head while I wrote. I didn’t let myself consider what my family or my husband’s family would think of what I was writing and I didn’t let myself think about the actual people I was writing about either. If had let any of those people into my head, I would have been too self-conscious to write effectively.

Lastly, I knew that in order for this to be a book that is helpful to others, which is what I want from it, I had to be able to say things that other people are scared to say. Facing my own darkest thoughts and putting them on the paper wasn’t easy, but I wanted to be brave enough to give voice to the pain and fear that so many of us feel but are afraid to talk about.

TMR: Word on the street is that you’re working on your second book…can you share any details?

CBS: I am indeed working on a second book. It’s a spiritual memoir, tentatively titled After This, in which I attempt to figure out what I believe happens when we die. I go into the journey having no real firm belief on what happens next, and through a series of experiences and research I aim to come out of it with a better understanding of where my parents are and where I might be headed when I leave this world. This book is born out of a desire to impart something useful to my daughter when she asks me what happens when people die, and it’s also an attempt to feel peaceful about all those who I’ve lost. So far I’ve delved into Kabbalah, visited psychic mediums, been hypnotized for past life regression and been counseled by priests. It’s been a fascinating journey so far and I look forward to moving forward.

TMR: Is there any singular piece of advice you have for others who are navigating the process of writing a memoir?

Tré Miller Rodríguez lives in Manhattan and her first book, “Split the Difference: A Heart-Shaped Memoir,” is currently under consideration by publishers. To read excerpts, please visit WhiteElephantIntheRoom.com.

Comments

Post a Comment

We would love to hear from you but hope you are a real person and not a spammer. :)